Laura Vang Rasmussen of the University of Copenhagen can finally wipe the sweat from her brow. For the last four years, she has served as the link between 58 researchers on five continents and as lead author of a major agricultural study which gathered data from 24 research projects, along with colleague Ingo Grass of the University of Hohenheim in Germany.

The hard work has finally paid off. Their research article, just published in the prestigious journal SCIENCE, delivers a clear and well-founded message to agriculture:

"Drop monoculture and industrial thinking and diversify the way you farm – it pays off," as Laura Vang Rasmussen from the Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management puts it.

Grazing rotation on a small farm in Columbia. Photo: Juan Arrendondo

"Our results from this comprehensive study are surprisingly clear. While we see very few negative effects from agricultural diversification, there are many significant benefits. This is particularly the case when two, three or more measures are combined. The more, the better, especially when it comes to biodiversity and food security," she explains.

Agricultural diversification: Strategies and practices

The research article has collected data on the effects of more than 20 different types of diversification practices within five broad categories of diversification.

Diversification strategy

List of practices

Temporal crop diversification:

Rotation

Rotation including > 2 crops

Cover cropping

Non-crop diversification:

Hedgerows

Windbreaks

Flower strips

Beetle banks

Forage strips

Other non-crop diversity

Soil conservation:

Manure application

Compost application

Green manure application

Inoculant application

Biochar application

Residue incorporation

Mulching

Nutrient mobilizing plants

Other beneficial soil amendment practices

Livestock diversification:

Number of livestock species, including e.g., cattle, horses, pigs, goats, sheep, fowls, donkeys, fish, and managed bees

Water conservation:

Terracing

Continuity of cover/roots

Bunds

Contour farming

Other beneficial water conservation practices

The researchers see the greatest positive effects on food security, followed closely by biodiversity. Furthermore, social outcomes in the form of well-being also improved significantly.

Among the many strategies adopted, livestock diversification and soil conservation had the most positive outcomes.

Yields not hampered– with clearly improved food security

According to the researcher, previous studies investigated either the socioeconomic or environmental effects of agricultural diversification. This study investigates effects across the board, with surprisingly positive results.

"Agricultural diversification has been accused of perhaps being good for biodiversity, but having a few negative aspects too – especially with regards to not being able to achieve sufficiently high yields. But what we actually see, is that there is no reduction in yield from diversified agriculture – not even when we include data from large-scale European agriculture," says Ingo Grass of the University of Hohenheim.

Polyculture strawberry field lined by a flower strip. Photo: Claire Kremen

In fact, the figures demonstrate that in the case of small farms and farms with lots of cultivated land in the surroundings, more diversified agriculture can significantly promote food security. This, according to the researchers, could be due to a number of factors.

"One example is fruit trees planted in maize fields in Malawi, which can help farming families improve their food security through improved diet and nutrition. Partly because they eat the fruits themselves, and also because the trees generate extra income when their fruits are sold at market – income that provides small-scale farmers with purchasing power for other foods," says Laura Vang Rasmussen.

Massive amount of data revealed win-win outcomes

All 58 of the study’s authors participated actively in its design to attempt a robust and credible interweaving of the many data sets spread across the world – from maize production in Malawi, to rubber trees in Indonesia, to silvopastoral cattle farming in Colombia and winter wheat in Germany.

Unique study design involved researchers worldwide.

With 58 researchers scattered around the globe, all of whom have been involved in the design of the study and the interweaving of their 24 datasets from other studies – representing a total of 2655 farms on five continents – the research project is quite unique.

"As far as I know, this has never been done on such a scale before. Finding common indicators for these calculations, in so many different studies and diverse data, and in such a way that we were able to integrate them, has been hard work. But I think the approach may inspire future research. That the enormous amount of data we processed provides such clear results is quite groundbreaking," says Laura Vang Rasmussen.

"The study unites many different situations from the many data sets that we used. In Malawi, we have data on food security expressed, for example, in the number of hungry months for small-scale farmers where they have been short of food. Such metrics are not used for, for example, large European farms, where we have yield data instead, such as winter-wheat yields in Germany, explains Rasmussen, who continues:

"But the point is that when we look across all datasets, our results show that applying more diversification strategies improved both biodiversity and food security, and didn’t have a negative effect on yields."

The researchers also investigated which diversification strategies result in 'pairs' of favorable “win-win” outcomes. Their data showed that strategies beneficial for biodiversity also improved food security.

They also witnessed win-wins for biodiversity and people's well-being.

Effects with and without natural areas in surroundings

To investigate whether the surrounding landscape influences the effects of diversification strategies, the study also took three different types of landscapes into account: heavily cultivated areas with very little nature, an in-between “simple” category with mixed landscapes, and areas where the landscape around farms is characterized by nature that is relatively pristine.

Facts: Three types of surrounding landscapes

The study investigated whether the degree of natural habitat in the surrounding landscape moderates the effects of diversification:

- Cleared Landscapes: <5% semi-natural habitat in a given landscape

- Simple Landscapes: 5-20% semi-natural habitat in a given landscape

- Complex Landscapes: >20% semi-natural

habitat in a given landscape

Until now, the thesis has been that diversified agriculture would only have a very good effect on biodiversity for in-between or “simple” type landscapes, which is also where the researchers recorded the greatest effects.

But in fact, the study shows that diversification strategies make good sense in many different contexts. Even in landscapes with more nature, there are positive effects to be gained with regards to biodiversity.

"It's a simple message to be able to pass on to different types of farms – whether it is small farms in South America or Africa or advanced European agriculture, there are lots of positive effects to be gained by introducing these various strategies – and very little to fear. It is very positive that so many different things can be addressed, and that, in general, positive biodiversity outcomes seem to go hand in hand with well-being and food security," says the Ingo Grass.

Extra info: Few negative effects may be temporary

The study found very few measurable negative effects resulting from diversification efforts. One of them was in connection with the category "non-crop-diversification", e.g. planting of trees on farms. Data show that these activities can affect farms specifically with regards to well-being – or quality of life, but this may be a transitional period.

"We cannot say with certainty what is driving this, but it may be due to the increased labour required to plant and maintain trees on farmland. This could manifest itself as a negative effect on well-being. One explanation could be that it takes time to reap the rewards of having trees on farms. So, whereas planting trees takes an immediate toll on the labour requirements, it takes years before the fruits of the trees can be harvested," says Laura Vang Rasmussen.

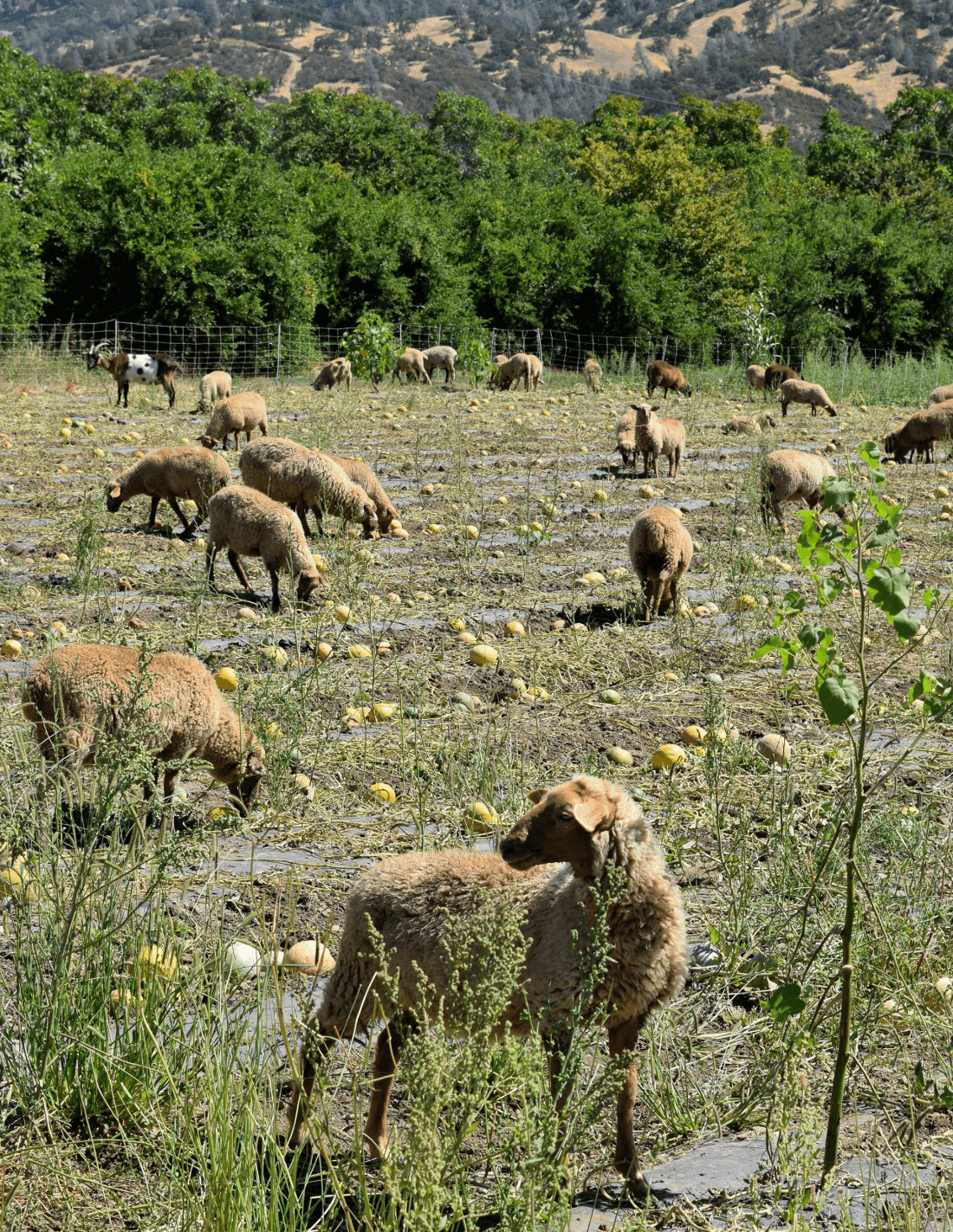

Sheep cleaning up an old crop field. After the harvest farmers send the sheep to help clean up remaining crops, consume weeds, and fertilize. Photo: Olivia Smith

This is backed by Professor Zia Mehrabi from the University of Colorado Boulder and Professor Claire Kremen of the University of British Columbia who are the joint PI’s of the study:

“This is an important achievement in bringing together some of the world’s foremost agricultural researchers to synthesise the data needed to back policy on driving the transformations that are needed in farming landscapes,” says Professor Zia Mehrabi. He is joined by Professor Claire Kremen of the University of British Columbia:

“The study shines a light on real-world farming conditions in many different regions and contexts worldwide. With the clear positive outcomes of these diversification strategies it suggests that governments and businesses should invest more in incentivizing farmers to adopt such strategies, which will in fact help them while also promoting agricultural sustainability and planetary health,” she says.

Behind the research:

Laura Vang Rasmussen from the University of Copenhagen and Ingo Grass from the University of Hohenheim, Germany, are joint first authors of the study.

Professor Zia Mehrabi, at the University of Colorado Boulder and Professor Claire Kremen of the University of British Columbia are joint PI’s of the study. They helped bring together the international research team at the NSF funded National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center, in the United States.

See the rest of the extensive author list in the study: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adj1914