The Arctic tundra is a cold, vast wilderness that has served as a carbon sink for a very long time thanks to low temperatures and moist soil. Soils in tundra ecosystems store nearly twice as much carbon as is stored in the atmosphere.

But as Arctic temperatures rise rapidly, carbon in tundra soil and plants will be released as CO2 much more quickly as well. In fact, 30% more CO2 on average will probably be released from tundra ecosystems when air temperature rises 1.4°C from today’s values. This has been demonstrated in a major new study that University of Copenhagen researchers participated in and has just been published in Nature. The 30% increase is far more than estimates from previous studies.

"We were well aware that we’d likely see increased CO2 emissions from the tundra with global warming. But our new study reveals a startling increase that is nearly four times more than previous estimates," says Professor Riikka Rinnan from the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Biology.

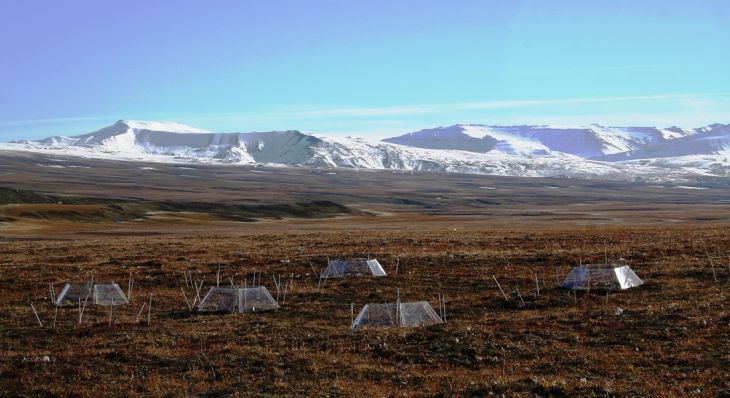

The researchers were able to measure the emission and absorption of CO2 by enclosing a small part of an ecosystem

The researchers were able to measure the emission and absorption of CO2 by enclosing a small part of an ecosystem(photo: Riikka Rinnan)

The team behind the new results, which includes more than 70 scientific researchers from around the world, synthesized data from climate experiments at 28 different tundra sites on four continents. In the study, researchers tried to simulate the climate of the future in small open-top chambers that served as mini greenhouses to create local warming.

ABOUT THE STUDY

- Climate experiments in Open-Top Chambers (OTCs) led to a 1.4°C increase in air temperature and 0.4°C increase in soil temperature, together with a 1.6% decrease in soil moisture compared to the conditions in the control areas outside the OTCs.

- These changes boosted the experimental ecosystem’s release of CO2 by 30% during the growing season compared to control areas without warming. The effect could be measured for at least 25 years – which is as long as these trials have been underway.

- Some of the experiments in the study were able to determine whether the extra CO2 released from the tundra comes from plants or from the soils and microbial communities within them. The result was that the release increases from both sources.

- The research article has just been published in the journal Nature.

- The study was conducted by a large international research team headed by Umeå University (Sweden). Contributing University of Copenhagen researchers were Riikka Rinnan, Bo Elberling, Anders Michelsen, Cecilie S. Nielsen, Emily P. Pedersen, Casper Tai Christiansen, Nynne Marie Rand Ravn and Ingvild Ryde.

The researchers analysed the amount of CO2 emitted into the air by each ecosystem through respiration – when plants and soil microorganisms breathe. They then compared the measurements from the open top chambers with measurements taken outside them.

The new study demonstrates that two sources contribute to an increased release of CO2 from the tundra: higher temperatures cause soil microorganisms to metabolize carbon in the soil faster and release it as CO2. At the same time, warming accelerates plant growth and respiration from plant roots.

CO2 increase continues for 25 years

The study also demonstrated that the increased CO2 release from a warmed tundra ecosystem continues for at least 25 years:

"There is no evidence that the increased CO2 emissions in a warmer climate will decrease over time. One might imagine that the release would lessen as some carbon disappears – but that is not the case. Some of the experiments in the study have been running for 25 years, and our conclusion is that the tundra just keeps on releasing carbon," says Riikka Rinnan.

"The study also shows the importance of long-term Arctic field studies, where researchers from the University of Copenhagen have contributed with data from both Greenland and northern Sweden," says Professor Anders Michelsen, another participant from Department of Biology.

Photo: Matteo Petitbon

Can tundra go from carbon sink to carbon source?

The results show that local soil conditions, such as nitrogen content and soil acidity (pH), influence the degree to which an increase in temperature will affect the release of CO2. Across the 28 tundra sites where the experiments took place, the highest increases in CO2 release was observed for areas with the least amount of nitrogen in their soils. This was especially true in parts of Canada and Siberia.

"This is surprising because both plant growth and the decomposition of accumulated carbon in soil are typically greatest when there is an abundance of nitrogen in soil. Thus, the new research also indicates that there are a number of unresolved questions to address before we fully comprehend the Arctic tundra’s carbon balance," says co-author Professor Bo Elberling from the Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, adding:

"If soil carbon decomposes faster than it is renewed by increased plant growth, the tundra could end up being a source of CO2 in the future. And that, in turn, could exacerbate the effects of climate change. So, it is important that this study be followed up by reports of how much CO2 the tundra absorbs through increased plant growth."

The study, which is the largest of its kind to date, is a reminder of the forces at play in the climate, as Riikka Rinnan concludes:

"Our results are a reminder to us all that while we can control anthropogenic sources of CO2 – which we should – other sources of CO2 are 'out of control'. But it is important that we take these emissions into account when trying to predict the climate of the future. And the new knowledge we’ve gained here can be used to improve the accuracy of climate models."