Thirty years ago, in 1993, Britain’s Prime Minister morphed into a man-sized dragonfly larva.

This memorable punishment, meted out by Ted Hughes’ The Iron Woman, comes as revenge for the ‘thoughtless’ pollution of rivers, lakes and seas, which his fable’s giant heroine has come to call home.

Hughes, an alumnus of Pembroke College, loved wild fish and rivers, and campaigned to protect them both before and after he was appointed Poet Laureate in 1984.

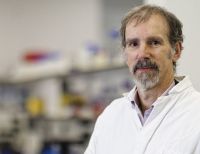

“He would have been in despair”, says Mark Wormald, Lecturer at Pembroke, Chairman of the Ted Hughes Society, author of The Catch: Fishing for Ted Hughes, and co-organiser of the conference ‘Owned by everyone? The wonder, plight and future of chalk streams’.

“Ted wasn’t just an extraordinary poet of the natural world. He knew his rivers and his science,” says Wormald. “He observed the deteriorating health of our rivers and he waged a campaign to save the Torridge, Tarka the Otter’s river in Devon, from exactly the same stress points that our rivers are still suffering from today.”

From sewage-dumping water companies to agricultural chemical runoff, England’s rivers have been making headlines for all the wrong reasons in 2023, and the country’s chalk streams have been centre stage.

Described by David Attenborough as “one of the rarest habitats on Earth” in his recent BBC series Wild Isles, chalk streams are under serious threat and with 85 per cent of them located in England, the eyes of the world are on this most English and deceptively idyllic of battlegrounds.

The country’s 220 chalk streams are distributed across a fan that opens in North East Yorkshire and closes in Dorset.

Fed by aquifers in chalk hills sixty million years old, they provide naturally gin-clear, nutrient-rich waters which support an astonishing array of species, including water crowfoot and starwort; mayflies, stoneflies, damselflies and dragonflies; wild trout, grayling, bullhead and minnows, with sea trout and salmon in some ; kingfishers and bats; otters and water voles.

Wild trout. Image: Charles Rangeley-Wilson

Wild trout. Image: Charles Rangeley-Wilson

But these ecosystems are under strain. Water crowfoot is being replaced by blanket weed and algal blooms because of dredging and pollution. Aquatic insects cannot reproduce when chalk streams lose water flow and depth, partly caused by excessive abstraction by water companies.

Water crowfoot. Image: TeunSpaans

Water crowfoot. Image: TeunSpaans

When invertebrate populations decline, this depletes a vital food source for wild fish. At the same time, fish are struggling to breathe in chalk streams robbed of their flow and cannot breed where gravels are no longer being washed clean.

In March 2023, Pembroke College, Cambridge Conservation Initiative (CCI), and the charity WildFish Conservation hosted a conference designed to mobilise support for Britain’s chalk streams. Held in Cambridge’s David Attenborough Building, the event attracted almost a hundred scientists, writers, artists, river keepers, land owners, representatives of community action groups and leading NGOs, politicians, and even key figures from British water companies.

The event proved timely, sandwiched as it was between a wave of media coverage about water companies releasing sewage into rivers, and a government pledge to lift the cap on fines for those offences. While some campaigners welcomed the announcement, most insisted that far greater action is needed to save the nation’s rivers.

Leading figures in British river and wildlife conservation spoke at the conference including Tony Juniper, Chair of Natural England; Fergal Sharkey, a leading voice in the campaign against river pollution; and Amy-Jane Beer, a biologist, writer and conservationist. The event’s opening session was chaired by Lord Chris Smith, formerly Chair of the Environment Agency, and currently Master of Pembroke College, as well as Chairman of South Staffs and Cambridge Water Company.

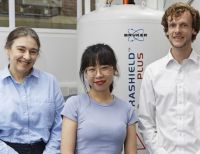

Among the first to speak were Mark Wormald; Catherine Sayer, freshwater biodiversity lead for the IUCN Biodiversity Assessment and Knowledge Team (part of CCI); and Tom Worthington, an aquatic ecologist from Cambridge’s Department of Zoology.

Shortly before the event, I met them by the banks of the River Cam, Cambridge’s very own chalk stream, to discuss their work and passion for chalk streams.