Skyscrapers, bridges, ships, aeroplanes, cars – everything humans make or build sooner or later decays. The ravages of time are known as corrosion; nothing is safe from it.

This makes the fight against corrosion expensive. All countries together invest around 3.5 percent of annual global gross domestic product in corrosion protection, which amounts to some 4,000 billion dollars: a huge market – and a gigantic problem.

Researchers at ETH Zurich led by Markus Niederberger and Walter Caseri from the Laboratory for Multifunctional Materials have now presented a new solution. Over the past years, they have developed a plastic that could greatly improve and simplify corrosion protection. Poly(phenylene methylene) is the miracle material’s name, or PPM for short.

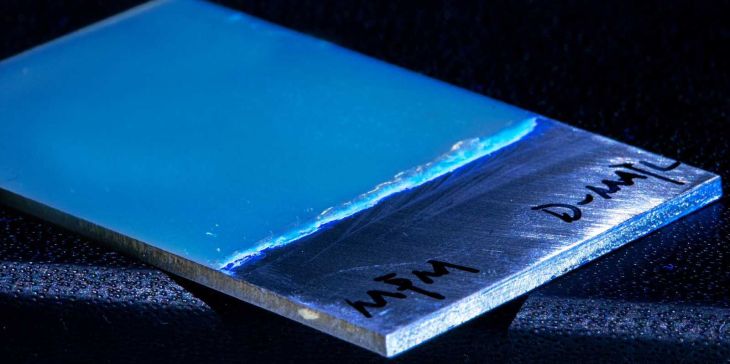

This new corrosion protection material kills several birds with one stone. When mixed as paint and heated, PPM can be sprayed onto a surface and becomes solid. The polymer indicates holes and cracks in the protective layer by failing to fluoresce.

What’s more, it repairs any damage itself without further external intervention. And at the end of a product’s life, the polymer can be completely removed and recycled with only minimal material loss. The recycled polymer can then be applied to another surface with no loss in its special properties and functions.

Chance gave a helping hand

It was pure chance that kicked off this development. About ten years ago, researchers in Niederberger’s lab were working on the production of nanoparticles in a special organic solvent. Under certain conditions, the solvent became solid: it polymerised. “That was unintentional and unwanted,” Niederberger recalls. “We didn’t know what to do with it at first either.”

But then they discovered that the polymer they had created by accident – known as PPM – had another interesting property in addition to its high thermal stability: it fluoresced even though conventional knowledge suggested it should not be fluorescent at all. And so the researchers specifically refined the material. First, a doctoral student improved the polymer’s synthesis. After that, his successor, the doctoral student Marco D’Elia, was given the task of finding a useful application for PPM.

“And he did this job with flying colours,” says a delighted Walter Caseri, who supervised D’Elia. His contacts with corrosion experts at the Università degli Studi di Milano also proved fruitful, Caseri says.