As well as studying abnormalities in brain development, Treutlein’s laboratory is also working on the Human Cell Atlas, a project that aims to draw up a map of every cell type in the human body, from development to adulthood. Researchers around the globe are putting immense effort into creating this reference atlas.

The main contribution from Treutlein’s research group is data obtained from characterising the cells of the nervous system. In their experiments, the team analyse more than 20,000 genes per cell, repeating this process for thousands of cells. This generates vast quantities of data, which the scientists interpret with the help of machine learning. “The algorithms spot patterns within this huge volume of data,” says Treutlein. This information is then added to the reference atlas, which researchers worldwide can use for experiments.

Cells form patients

Some of the organoids in Treutlein’s lab are derived from embryonic stem cells (ESCs), which international organisations have been preserving as stem-cell lines for decades. Because ESCs emerge very early on in the development of the embryo, they can be used to produce any type of cell – given the right environment – and thus any type of organoid.

The research group also generates its own stem cells from adult tissue. Known as induced stem cells, these are produced from body cells such as skin cells or white blood cells. By introducing the right factors into these body cells, they can be turned back into stem cells, which can then be used to grow a new organoid. “We can isolate cells from patients, transform them into stem cells and then generate an organoid,” says Treutlein. “What makes this approach so exciting is that we’re essentially mimicking organ development on the level of the individual patient.” Using this method, researchers can model how a disease develops in a Petri dish and try to understand the mechanisms involved.

Periventricular heterotopia is one such disorder that is currently being studied by a doctoral student in Treutlein’s research group. This is a condition in which the neurons fail to migrate properly during the initial development of the cerebrum. Epilepsy can be one of its manifestations. Scientists know that 21 genes are affected. When they switch off these genes in the brain organoid, this creates an imbalance in the different cell types. For now, these are still just the preliminary findings from initial experiments. “But if we can improve our understanding of the mechanisms involved, that could lay the foundations for new therapies,” says Treutlein.

More than one cell type

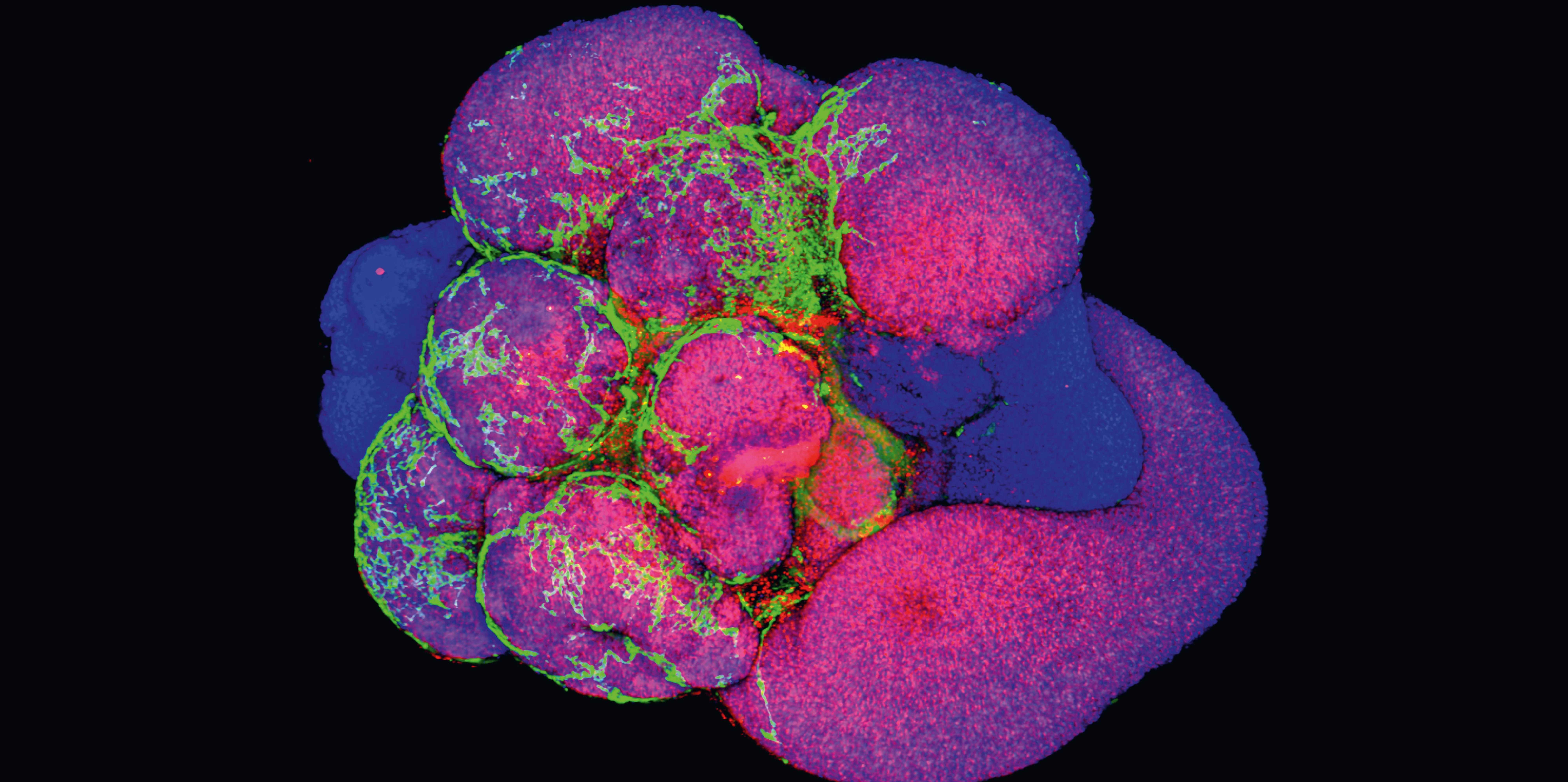

Treutlein’s research group has analysed the individual cells of the tumouroids. Unlike analysis under the microscope, which merely permits a generalised pronouncement as to whether the tumour tissue is dying or not, Treutlein’s single-cell technology yields much more precise conclusions. “Organoids are complex structures,” she says. “That’s why it’s important to analyse them in detail.” By analysing genes and proteins at the single-cell level, scientists can determine how efficiently a cancer therapy works on a tumouroid.